Nicole Pacino

Nicole L. Pacino is an associate professor of history at the University of Alabama in Huntsville. Her research interests include twentieth-century Andean history, the history of public health, revolutions and social movements, and gender. Her work has been published in journals based in the United States, Europe, and Latin America, including Diplomatic History, the Journal of Women’s History, the Bulletin of Latin American Research, and História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos.

Working with Primary Sources

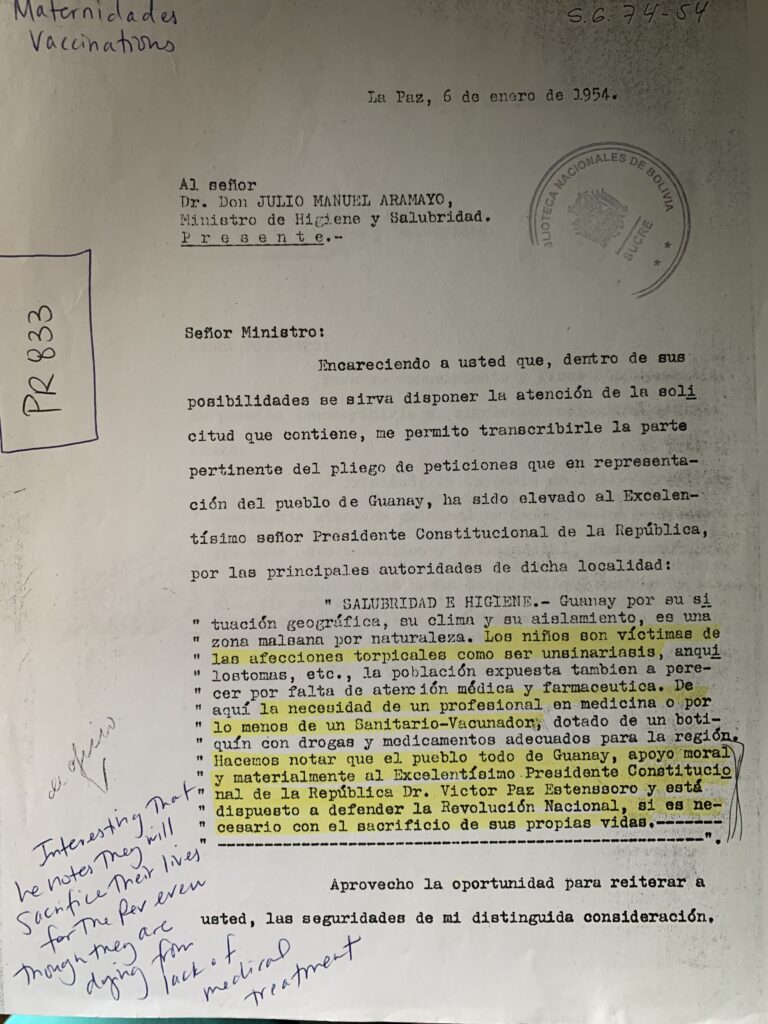

This is an excerpt of a letter sent to federal government by the community of Guanay, located in the Yungas region (north of La Paz), in January 1954. The Health Ministry received the following pertinent segment:

“Guanay, due to its geographical location, climate, and isolation, is unhealthy by nature. The children are victims of tropical diseases like hookworm, etc. The population is at risk of perishing due to a lack of medical and pharmaceutical attention, hence the need for a medical professional or at least a sanitary-vaccinator equipped with a first-aid kit with adequate drugs and medicines for the region. We note that the entire community of Guanay supports the president Víctor Paz Estenssoro morally and materially and is ready to defend the National Revolution with the sacrifice of their own lives, if necessary.”

This source comes from the National Archive, located in Sucre, and is part of the Presidencias de la República correspondence files.

Source Description/Analysis:

For rural communities, the revolution presented an opportunity to make demands on the state. Rural communities began to see public health as both a state responsibility and a personal right. They also recognized state rhetoric as a form of political currency that they used to frame requests for doctors, hospitals, and medicines in letters that the presidential office received by the hundreds annually. The revolution provided the language to demand state accountability to local needs. Public health was inextricably intertwined with post-revolutionary state formation because rural communities astutely manipulated state rhetoric to advance their own agendas and underline their contribution to the revolutionary project.

Communities often packaged demands for clinics, doctors, and medicine in the rhetoric of revolutionary nationalism. This excerpt from the self-described “isolated” community of Guanay, illustrates this use of revolutionary rhetoric perfectly. Their January 1954 petition to the government called their children “victims of tropical infections like hookworm” and claimed that their population “perished due to the lack of medical attention.” They requested that a “medical professional” be sent to the community with medicine. The petitioners also noted that they supported the president and were “ready to defend the National Revolution with the sacrifice of their own lives, if necessary.”

This community was dying from lack of medical care but also willing to die for the revolution. How could people willing to put their disease-stricken bodies on the line to defend the revolution not be worthy of government assistance? This nationalistic language demonstrated supposedly isolated communities’ astute knowledge of national politics and ability to manipulate state rhetoric to draw attention to local needs in a way that demonstrated their political sophistication.

After two years of Paz Estenssoro’s presidency, rural communities could identify a language with which to package their requests for state attention and medical assistance. That Guanay employed the idea of political loyalty to request a health practitioner and medicine shows the two were inextricable. Communities like Guanay used public health as a bargaining tool, pledging political support in exchange for state services.

Excerpt from Nicole Pacino, “Bringing the Revolution to the Countryside: Rural Health Programmes as State‐Building in Post‐1952 Bolivia,” Bulletin of Latin American Research 38, no. 1 (2019): 50-65.

We thank Nicole Pacino for providing this source.